Doing Restorative Justice Education from the inside Up

- Felix Rosado

- Oct 5, 2021

- 15 min read

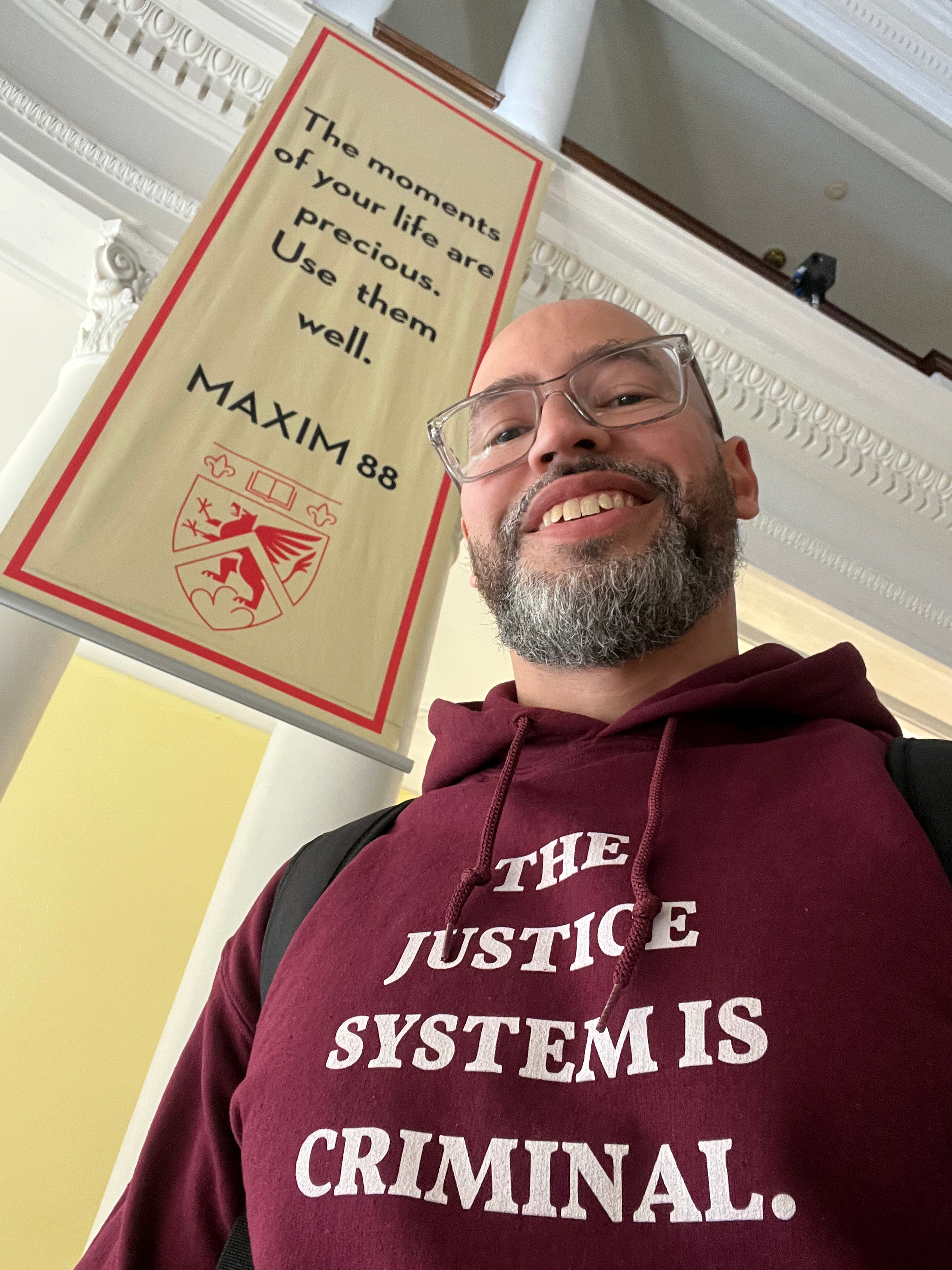

By Felix Rosado

“I’ve been doing this [prison]thing here all my life. I did every program the DOC got, some of them two, three times. And I never felt anything like this. I never before saw how much harm I did my victims, my own family, and the community. Everybody should have to take this.” --Mini Intro RJ Workshop participant, August 2017 “I think justice has to be done from the context up, from the community up. It should not be done from the government down.”

--Howard Zehr, Rooted in Respect

In 2007, at age 30 and twelve years into my death-by-incarceration sentence (more commonly referred to as life without parole), something drastic happened. Midway through a voluntary course I was taking through Temple University called Inside Out, I was assigned to read a photo-essay book titled Transcending: Reflections of Crime Victims. Alone one afternoon in a 6-by-12-foot cell, I sat on a thin foam mattress, hunched over, legs folded under me, and read one heartbreaking account after another. The eyes of those telling the stories penetrated mine. Their voices echoed within the four concrete walls. Suddenly, for the first time, I was face-to-face with a hard truth: I, Felix Rosado, caused similar pain to a family somewhere out there with eyes, voices, and stories of their own. I cried—and was never the same. At the end of the book, the author, Howard Zehr, talked about this thing called restorative justice, a different, but not necessarily new, way to address harm that seeks to heal by involving those most affected--including those who caused the harm. Yes, I thought, that’s it! The story of my crime did not have to end on sentencing day. There was still more to write. Shortly after, Charles Boyd, also fighting a death-by-incarceration sentence, and I worked to hone a 10-session restorative justice (RJ) education workshop he had just developed and piloted. That initial workshop, with the help of too many to name, has evolved into a project and movement that ten years later has touched over a thousand lives directly and countless more by extension. The basis for this movement, which we have since named Let’s Circle Up (LCU), has always been that we all need to be included in working through our own problems and that when we harm others, we have an obligation to put things more right. Our Intro RJ Workshop, which was adapted nonstop and completely overhauled once during the first six years, focuses on rethinking our mostly depersonalized and oversimplified perceptions of crime and justice, exploring the real impact of crime and other harms, examining our own personal values, and introducing us to RJ values, principles, and practices. We use a variety of creative and highly interactive learning experiences to accomplish this, all the while forming a safe enough or “brave” space where the stories and wisdom of each circle member can be drawn forth and absorbed by everyone sharing the space.

There is invaluable worth in the lived experience of everyone who sits in our circles. Since we all learn and share in different ways, our separate-yet-connected learning experiences provide a variety of opportunities for us to tap into the many years of life lessons contained in the circle, while engaging both sides of our brains. Some experiences involve movement around the room so that we are using our bodies in addition to language to express our thoughts. One particular experience, Human Continuum from our Rethinking Crime and Justice session, asks us to position ourselves along a line in response to a series of this-or-that questions, giving us a visual of the diversity of perspective in the room. We read, draw, watch videos, role play, and mostly importantly, talk. We talk in pairs, triads, small circles, large circle. We experience first, then process. In the processing of each experience, we create meaning—together. We believe learning should be fun. And in LCU, without losing any of the seriousness of the topics we explore, most people say it is. By the time we ask each group to develop its own workshop guidelines midway through session one, everyone can tell that something out of the ordinary is taking place. Here, the group has hands on the steering wheel. For instance, in our RJ: a Different Approach session early in the workshop, we share an experience called Re-Imaging Justice in which we take a critical look at Lady Justice and then draw (literally) and present our own images of what we believe justice should look like. At this stage in the workshop, most participants still find it hard to envision the concept of justice outside the confines of police officers, courts, and prison cells. But together we begin to conceive an alternate path to addressing harm and doing justice. Later in the workshop, during our Exploring Harm session we do an experience called Four Corners that helps us examine the complexities of crime and begin to view crime as not just the breaking of laws in the abstract but as real harm caused and experienced by real people. We hang up four signs, one at each corner of the room, that read “Strongly Agree,” “Agree,” Disagree,” and “Strongly Disagree.” We then reveal a series of seemingly simple, yet complex prompts, such as “Harm cannot be repaired” and “Harmed people harm people,” that take us each to the corner that best reflects our position on each statement. In those corners we discuss why we took that position and then a representative from each shares with the room a summary of the discussion. Through this, we get to hear a diversity of perspectives and see how complicated issues around harm and crime truly are.

Later on, in our Doing RJ session, we examine accountability through a word association experience known as a wordstorm. The word “accountability” gets put on the board and the group calls out the first words that come to mind, uncensored, in response. Once the board is full, we attempt to make sense of what we have come up with. As a result, we begin to see accountability beyond the walls of a prison cell and make the distinction between being accountable and being held accountable. In the end, we usually conclude that “doing time”—at the outside community’s immeasurable expense—does not necessarily translate to true accountability. Rather, we see that coming to terms with the harm we have caused and trying to do something to put things more right is much more beneficial--and just—to everyone affected and more like the “paying a debt to society” that prison is usually referred to as.

A topic that usually does not get touched on in most staff or outside volunteer led victim awareness/crime’s impact-type classes is the effect of our crimes and incarceration on our families. In LCU, because we are best able to identify our own needs, we create ample space to explore this. An experience called What Does Justice Require? in our Just Questions? session asks one of three groups to consider the needs of the family of people who have offended in a provided scenario. This safely gives us a glimpse into how our own families experience our incarceration. The effects of our actions on our families come up in several other sessions as well. Also, for our alumni, we offer a workshop called A “More Right” Legacy in which we watch and discuss a video, Shadows: Children, Families, and the Legacy of Incarceration, and then journal to a prompt that asks us to begin writing a letter to a family member or other loved one who has been impacted by our imprisonment. We often hear that one of our sessions or workshops has inspired participants to initiate a much needed conversation with family members about the pain that too often goes unrecognized or unspoken, to everyone’s detriment. At first Charles and I did all the enrolling, facilitating, and coordinating of the workshops on the inside, while collaborating with a team of three outside volunteers who provided material resources and participate in the weekly sessions. Through word of mouth, news of the workshop began to spread across the small city-like prison that holds about 4,000 residents and 1,200 staff. We quickly found ourselves collecting names and numbers scribbled on tiny corners of paper from men everywhere we went in the prison. We decided early on not to post flyers on walls or ads on the in-house prison channel as other groups do. Instead, we build relationships. We meet people where they are, literally, whether walking down the main corridor, in the yard, standing in the commissary line, at a chow hall table, or on the cell block waiting for a phone to open up. These initial encounters and the “pre-meetings” (as we call them) that follow give us the opportunity to not only begin building these relationships but to learn if someone is prepared to engage in the deep self-examination inherent in the workshop and with sensitive topics such as injustice and victimization, caused, experienced, and/or witnessed. We try to put the same amount of time and care into these pre-meetings as would go into preparation for any other common RJ practice, all within the confines of a maximum security prison. Our vantage point within the prison setting has given us the necessary experience and understanding to grow a workshop into a full-fledged project and movement—against a daily barrage of roadblocks and ceilings. We have lockdowns, late counts, trouble with getting passes issued. Upcoming participants might transfer a day or two prior to a workshop beginning, something only we would know, leaving us scrambling to quickly replace them. LCU requires grit. We also have to work closely with staff to help negotiate all the barriers that inevitably arise whenever it is time for a workshop which is year-round. Beginning a workshop on time with everyone in the room is a luxury we are hardly ever afforded. Still, we persist. We have persisted to the tune of over a thousand inside alumni as of this writing and another couple hundred people from the outside who have experienced one of our circles. We consistently work alongside 15-20 outside team members who have earned official volunteer status in the prison and countless other outside allies. Over time we expanded our leadership team and developed an advanced-level workshop (also 10 sessions) held twice a year, monthly activities for our alumni, and a Steering Committee to care for it all. Because our finger is permanently situated on the prison’s pulse, we are able to quickly adjust to the ever changing and highly unique circumstances of this complex environment in a way no one else can. For example, by 2013 the prison’s population had drastically shifted to a more transient nature as Graterford became a pit stop for hundreds of men a week from the southeast region of Pennsylvania who are rearrested for parole violations. We were in the best—and perhaps only—position to immediately realize this shift and adapt our 10-week Intro RJ Workshop into a 4-session, 2-day version that we have offered to 12-18 transient residents every month since, alongside the original four times a year. We began calling one the Extended and the other the Mini. Since most, and hopefully, all, of our Extended alumni will one day make the same transition home that our Mini alumni have already made, in some cases multiple times, our Restorative Integration subcommittee developed a workshop called Our Transition that brings together an equal number of alumni from both groups to have honest dialogue about what it takes to successfully transition from prison to the outside community. After an icebreaker, we have a Circle where we share our fears about transitioning home, a conversation that will rarely happen anywhere else. From there we brainstorm obstacles to successful integration and then come up with plans to overcome the most pressing of those obstacles. The presentations, developed in just a short period of time, always end up being world-class and worthy of large audiences. Unlike other “reentry” efforts that bring in “experts” from the outside to talk at us about our needs prior to and after release, we prefer to place our faith in the wisdom of the people with the lived experience who are better equipped to provide the expertise. We believe the best answers to our problems lie within us, and with the right structure and facilitation these answers can be drawn forth, resulting in the kinds of shifts in thinking that create real change. Including the voices of people who have been victimized in our circles is something Charles and I sought out since the beginning. Policy and politics during the early stages of LCU diminished our ability to have this physical presence in our circles. Since 2014, however, our work with the PA office of the Victim Advocate (OVA)* has led to several collaborations including a workshop developed and facilitated by some of our inside Steering committee members called Building Bridges, which includes LCU alumni and outside team members, OVA staff, and members of OVA’s Victim Speaker Bureau. Instead of what typically happens at a “victim impact panel” where people who have experienced victimization speak to a group of prison residents and then engage in Q&A, we use our interactive model of shared learning to guide the conversation through a series of experiences that progressively deepen as the comfort level increases. First, we get to know one another via a litany of one-on-one quick, lighthearted icebreaker conversations. Next, we set the stage for our guest speakers to share with a grounding and mediation experience. After the sharing, we move into small groups to collectively write poems in response to what was shared, which we go on to present and give to the speakers as a gift of our appreciation. After a break, we pull out markers and flipchart paper and shift to a group drawing experience that then sparks conversation about ways to create a world where needs are more regularly addressed and of less harm. After a usually tearful closing Circle, it is clear that something very different and transformative has just occurred—in a most unlikely of settings.

We agree with Dr. Zehr, and have experienced for ourselves, that justice must be done from the “community up,” and in the case of prison, from the “inside up.” We also believe that RJ education, if done experientially and collaboratively, is a true RJ practice in every sense. The encounter our workshops provide between circle members and the realities of victimization and other harms, while introducing us to a different approach to justice, can be as life altering as other familiar RJ practices. In fact, it can serve as the preparation needed for such a Victim Offender Dialogue, Family Group Conference, or Circle. However, in cases where facilitated face-to-face encounters are not possible, the RJ education we offer can result in some of the same outcomes. From the post-workshop questionnaires and plenty of verbal post-workshop commentary, we have heard over and over that alumni leave our Circles with expanded conceptions of crime and justice and new ideas for how to repair past harm and commit less harm moving forward. Though previously a foreign notion, the idea of meeting with the people we have hurt to apologize, answer questions, and attempt to put things more right, if appropriate, begins to seem possible and even desirable. Also, we begin to see justice as not just something to be left in the hands of the government or other authorities, but rather as something we can practice in our everyday lives. This alone is a major accomplishment. Our workshops provide hope in a place that, by design, leave little to reach for. We are trapped in a legal system, for better or worse, that prefers to focus on process and rule of law rather than the complexities and needs of the many human beings affected by each crime. From the moment a pair of handcuffs are slapped on, our current process begins to promote, implicitly and explicitly, silence and deception over truth. Immediately and inevitably our focus turns to fighting for our freedom and in some cases, our lives. There is no time or space to empathize with the people we have harmed or even begin to think about how to help them heal. In fact, walls, fences and policy in many ways prevent it. In an adversarial system scored by wins and losses, it is the people on all sides of the crime equation who usually lose. As a result, we can go years or even decades in prison never once having to think about the damage we have inflicted. For me, it took reading an assigned book in a voluntary course that just happened to be introduced to me by a friend to force me to deal with something I previously, and mostly unconsciously, avoided. LCU’s mission is to bring as many people as possible to similar turning points--well before their twelfth year. LCU takes people, who more often than not feel defeated, and empowers us all to see ourselves as change makers. In rooms all over Graterford, we circle up to build relationships, share our stores, and transform our minds and hearts. And, as we discover, our stories do not have to end with our worst moment. We need not be stuck at sentencing day. There is more story to write—and LCU hands each of our circle members a new pen. Unfortunately, this type of redemption is not a theme in our society’s collective imagination of crime and justice. Turn on any of the major broadcast networks during primetime any night of the week and some Law and Order-esque show will feature, with little variation, the following sequence: a bloody corpse, an hour’s worth of “good guys” trying to nab the “bad guys,” a climatic capture, maybe a court scene, and then the credits. This largely decontextualized narrative fails to include what happens next for the victimized and their families, those locked up and their loved ones, and the communities left to live in a constant state of aftermath. Unfortunately, for the millions who consume these and other media depictions of the criminal legal system at work, this represents reality. LCU takes up the messy business of what happens once the credits roll. In real life the story goes on well beyond conviction. We believe we are in the best position to appreciate this and act on it. While we have been able to accomplish a great deal over the course of a decade, it is important to note that Graterford is an anomaly across the “corrections” landscape. Here we have a long history of administrations that have supported and realize the value of resident created and led programming. As a result, something like LCU was able to take root and sprout truly from the inside up. Our brothers who come to Graterford from any of the other 26 Pennsylvania state prisons tell us that nothing like LCU can be imagined “up in the mountains.” Graterford’s close proximity to a large progressive city, Philadelphia, facilitates a constant stream of up to 200 outside volunteers who enter this wall at least weekly or monthly any given year to assist with programming and necessary resources, which are not included in the state’s corrections budget. If we must live in a world with prisons, we should be looking to models of justice that emphasize empowerment and self-determination over passivity and dependence. To get something like LCU stated elsewhere, we strongly suggest that the leadership arise from the inside up. Incarcerated people must develop curriculum based on the needs of their peers and particular setting. Relationships must be built with prison staff, perhaps starting within departments that might be interested in housing this type of project. Here at Graterford, LUC falls within the Substance Use Disorder (formerly Alcohol and Other Drugs) Department. This relationship has been crucial to LCU’s success. Also, solid working bonds must be forged with members of the outside community who are able and willing to volunteer time, energy, and resources to help sustain and grow the project. In other words, much groundwork must be laid prior to the first circle being assembled.

There is another main pillar that holds LCU up. Along with being led from the inside up, LCU workshops must be 100% voluntary. Many of our participants suggest to us at the end of workshops that our workshops should be mandated to everyone in the prison We understand and appreciate the sentiment behind the suggestion. However, the worst thing that could happen to LCU would be to remove one of our most core and unnegotiable principles: everything LCU must be done voluntarily and free of coercion, subtle or otherwise. Mandatory programs, as we know firsthand, do not encourage or inspire authenticity. This is why we have always done our own enrolling. Regardless of how well intentioned, even the suggestion by an authority that someone participate in a workshop can compromise this core principle. It is what separates us from prescribed programs. Everyone sitting in one of circles is there because they want to be. It makes all the difference when no one sits around staring at the clock, when no one leaves six months or more later not knowing who else was in the room. Built into our workshops is name learning and community building. Whether 10 sessions or 2 days, at the end everyone in LCU will know and share some bond with those who formed that circle with them. Relationship is first. Everything else stems from that. If we had to define LCU in a word, it would have to be relationship. From the relationship between the two founders to the relationship shared among the Steering Committee, our outside team, the Graterford administration and staff, and most importantly, everyone who sits in one of our circles—it is the thread that holds everything together. This ever-widening circle of relationship has spread to dimensions we can no longer see. When it came time to name ourselves after years of the default name Restorative Justice Project, we started by wordstorming RJP. During the processing, we clearly saw the theme of relationship running through the entire board in worlds such as “circle,” “community,” “together,” “us,” “people.” Throughout the discussion we kept coming back to circle. Our name would have to have “circle” in it. To close up the horseshoe we were sitting in and further discuss options for a name, the facilitator uttered the familiar words we have always used whenever it is time to form or re-form the circle: “Let’s circle up.” And there we had it. “Let us” represents the invitational nature of our work and the central role of relationship in all we do. And converting the word “circle” to a verb emphasizes that justice is something we must do. Our workshops are always designed to inspire action. To date, through our outside team and one recently released Steering Committee member, we have had three of our Mini Intro RJ Workshops on the outside. And with the publishing of our forthcoming facilitators’ manual and our plans for replication, our goal is to circle up as many communities as possible. We believe that RJ education, if done well and together, can build the kind of world we all long for, a world where harm is addressed in healthy ways by the people most impacted, where we see ourselves as interconnected and all worthy of respect, where accountability means more than laying on a thin foam mattress for years or decades. One Circle at a time, LCU is working towards a world where we no longer have to gather in prison classrooms, bounded by concrete and steel--but in homes, schools, houses of worship, workplaces, or on grass under the sun, where the only thing between us will be not walls but space, truth, and relationship.

*The Pennsylvania Office of the Victim Advocate is a state-run agency that provides assistance to people who have experienced victimization by anyone under custody of the Department of Corrections or the Board of Parole and Probation through a variety of services.

Comentarios